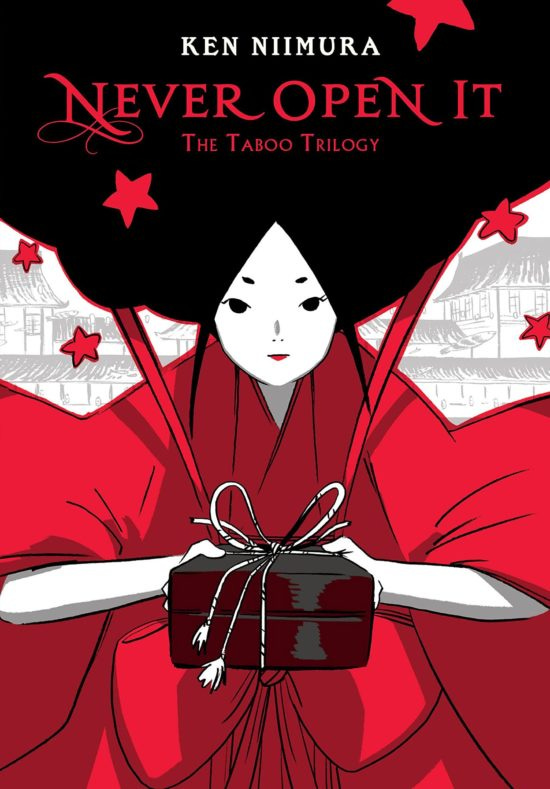

The Stories Behind Ken Niimura's Never Open It: The Taboo Trilogy

Why you'll never read Urashima Taro, Ikkyu-San and The Crane Wife the same way again

As part of this week’s Mangasplaining Extra focus on manga by Ken Niimura, we thought it’d be fun to take a deeper dive into the stories behind the three stories featured in Never Open It: The Taboo Trilogy by Ken Niimura, published in English as a one-shot graphic novel by Yen Press.

Before we get started…

If you’ve read Never Open It already, keep reading! If you haven’t yet read it (and I encourage you to pick it up) and want to read on, be forewarned that the rest of this essay is full of SPOILERS, both for the original Japanese folk tales and Ken’s version of these stories.

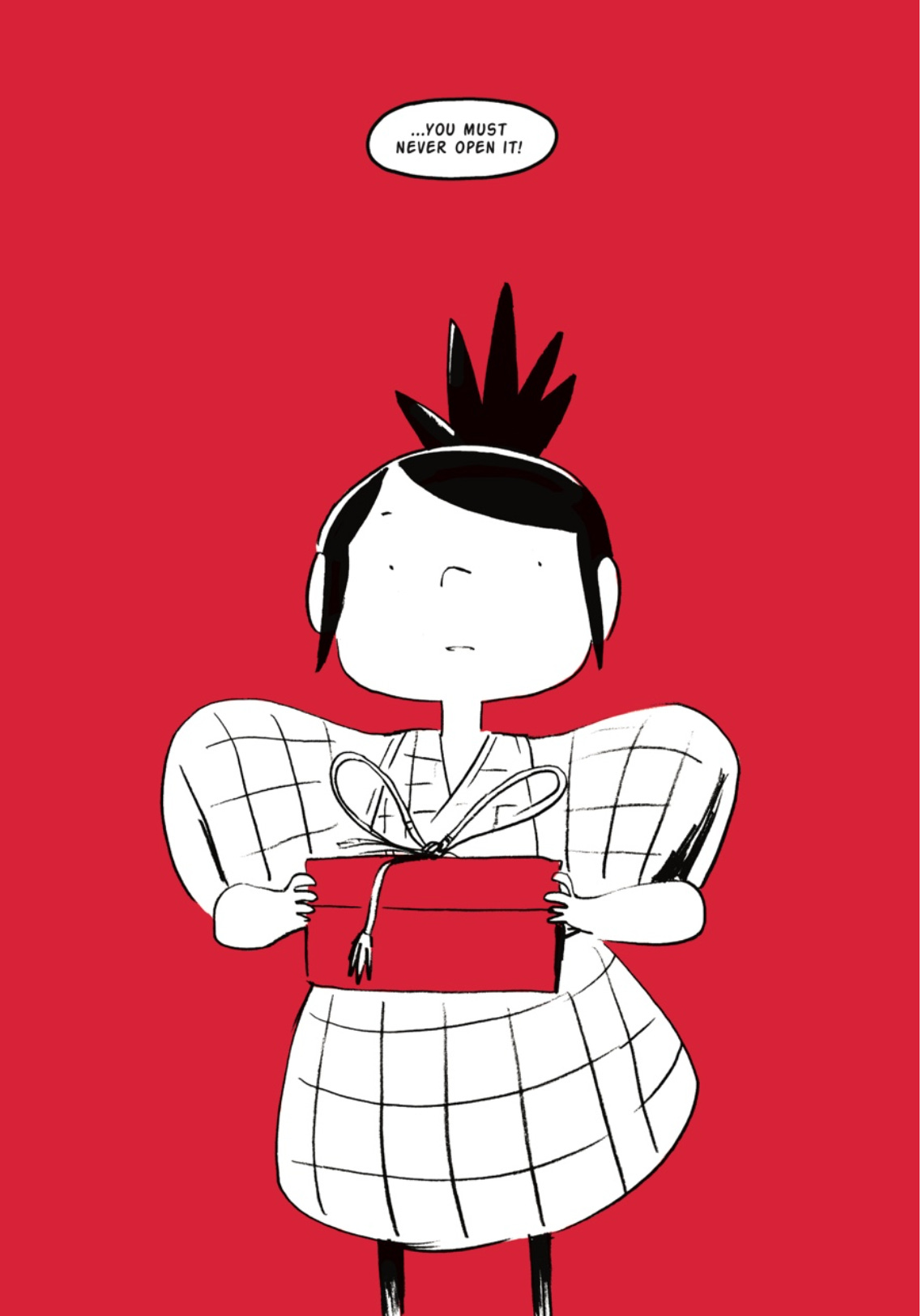

Okay, now that we’ve got that out of the way, as the title suggests, Never Open It is a set of three stories, all centered around a theme of a warning to the characters that they must not do something, or risk facing dire consequences later. In the case of first story, Never Open It, a young fisherman is warned to not open a box he has received from a sea princess. In the second story, Empty, a pair of Buddhist monks-in-training are warned to not peek into a covered jar. The title of the third story, The Promise refers to a vow that a young man makes to his wife to never peek into a room where she weaves cloth every night. Of course, in all three stories, these promises are broken, and stuff happens as a result! But how are Ken’s versions of these stories different than the original folk tales? Let’s break it down, one story at a time.

Never Open It – Urashima Taro

The first tale in The Taboo Trilogy is based on a classic Japanese children’s story, Urashima Taro. Set in an unspecified feudal Japan era, Urashima Taro is about a young man who lives with his mother near the seaside and works as a fisherman. One day, he sees some children tormenting a sea turtle on the beach. Taro intervenes and tells the kids to leave the turtle alone, then helps it return to the sea.

The turtle later returns and tells the young fisherman that as a reward for his kindness, Taro has been invited to visit the Dragon Palace, the home of Princess Otohime. He hops onto the turtle’s back and rides under the waves to an underwater paradise.

While at the palace, Taro enjoys fine food and drink, and entertainment fit for royalty. After reveling in a few days of festivities, Taro asks to return to the surface world. Otohime gives him a parting gift -- a lacquer box tied with a string that comes with a warning: He must never open it.

Taro returns to his seaside hometown and finds that things are not as he left them – his home is seemingly abandoned and dilapidated, his mother is nowhere to be found, and no one seems to know who he is. He figures out that while it felt like he spent only a few days under the sea, many years have passed. His mother died years ago, and he was presumed lost at sea. In despair and frustration, Taro ignores the princess’ warning and opens the box. When he does, the box appears to be empty, except for a mist that envelops him and instantly transforms him from a young person to a feeble old man.

I remember this story from when I was a kid – my grandmother read it to me from Japanese Children’s Favorite Stories, a collection of Japanese folktales collected by Florence Sakade and illustrated by Yoshisuke Kurosaki (published by Tuttle). I didn’t think much of it then, but now as a much older person reading this story, I’m left thinking, “Hey, Taro got a bum deal out of all that. He was a nice guy who helped a turtle. Just because he got invited to a party and had some fun, he got punished in that terrible way? That seems unfair.”

So maybe that’s why Ken’s version of Urashima Taro seems to right this wrong in a surprising way – or at least delve into the idea that maybe the sea princess did something kind of messed up in the original version of the story.

For the first chapters of Never Open It, the story pretty much proceeds as the original, although Ken adds more details about Taro’s daily life and his relationship with his mom. Where things veer off the well-established plot path of the original folk tale is when Taro returns from the sea and is tempted to open the box but is stopped just in time by an older fisherman who tells him that it’s a trick. This older man reveals to Taro that he too was a recipient of Princess Otohime’s “generosity.”

After this happens, that’s when payback time kicks in for the party-loving princess, as all hell breaks loose under the sea, and this kind of sad story gets a slightly different, maybe more satisfying ending.

Empty – Ikkyu-san and the Poison Candy

Now, the original version of this particular story isn’t featured in the Japanese Children’s Favorite Stories collection, but it does feature a character that I remember well from my childhood, albeit from a different source: from watching anime.

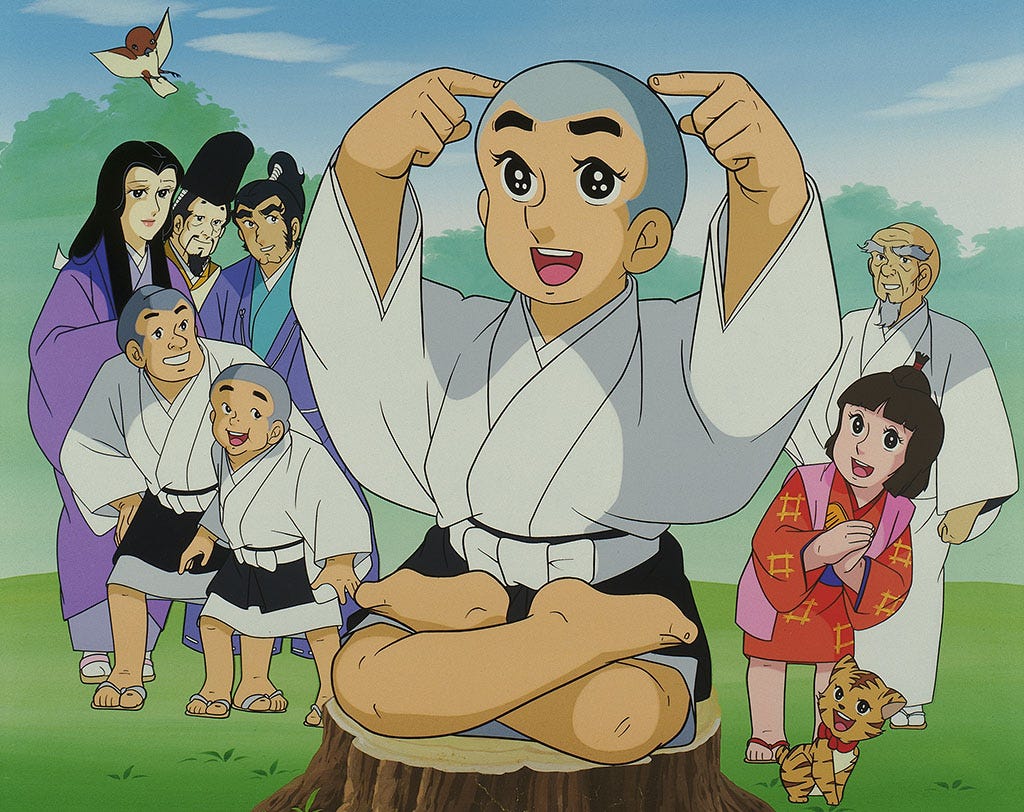

I grew up in Hawaii, so one of the animated shows that I saw on the local Japanese language TV station was Ikkyu-san, the adventures of a boy born into a nobleman’s family who became a Buddhist monk at a very young age. In the anime, he’s depicted as a precocious child who solves problems by tracing circles on this forehead, then meditating to come up with an often-unconventional solution.

Produced by Toei Animation, the Ikkyu-san anime series originally aired in Japan between 1975 to 1982 (over 296 episodes!), although it appears that it’s not currently available either via streaming or on DVD/Blu-Ray for the English language market. (Happy to be proven wrong, however! If you know otherwise, add your comments below!)

Ikkyu-san wasn’t just an anime character – he was a real person who’s also well-known to Japanese school children. While the anime does take considerable liberties with his life, Ikkyu-san, a.k.a. Ikkyu Sojun is a well-known figure in Japanese Buddhism. Born in 1394 as the son of Emperor Go-Komatsu and noblewoman, Ikkyu was separated from his mother when he was 5 years old due to political strife and sent to a monastery. He grew up to be a leading figure in Rinzai Zen Buddhism, who had a reputation for eccentricity, and questioning established beliefs and practices in Buddhism, including challenging the need for celibacy for monks.

One of the most beloved anecdotes about Ikkyu-san’s cleverness as a child is the tale of the “poison candy,” and that’s the basis for Ken’s story, Empty. In the original story, the abbot at the monastery has a jar of honey or sweets that he wants to prevent the younger monks from eating. So when the elder monk is called away from the temple, he warns Ikkyu-san and his fellow junior monks-in-training to stay away from the jar, because it contains poison. But curiosity gets the better of the young ‘uns and they open the jar to sample what’s inside.

After eating most of what was in the jar, the young monks dread the punishment they’ll receive from the elder monk when he returns. Ikkyu comes up with an unexpected solution: he breaks an expensive vase (or in some retellings of the story, a prized inkstone is broken). So when the abbot returns, Ikkyu apologizes for breaking the vase/inkstone and says that as penance, they all decided to eat the poison in the jar, but strangely, they haven’t fallen ill and died yet… why is that? The abbot is then forced to confess that he lied about the contents of the jar, and ends up forgiving Ikkyu and his fellow monks for breaking the vase/inkstone.

This illustrated video from the Japan America Society of Greater Cincinnati gives an overview of Ikkyu, including the story of the forbidden jar, the Shogun and the tiger on the folding screen, and highlights of his later life, including his relationship with a blind singer named Shinnyo, and the temple in Kyoto where he rests today.

Empty is a shorter, lighter, perhaps less ‘action-packed’ story than Never Open It and The Promise, which makes it kind of a palate cleanser between the other two tales in The Taboo Trilogy, but like the other two stories, Empty adds some fresh, different dimensions to the original story.

The basic premise is the same, but this time, the elder priest runs through a few ‘what-if’ scenarios in his head, including one where the jar of honey really does have poison in it. Realizing that young, curious boys will tend to do what you tell them NOT to do, the abbot comes up with a different solution to his dilemma.

Sure, this new twist doesn’t exactly give Ikkyu a chance to show off how clever he is, but it does give readers who might be familiar with the original a moment to consider that leaving a jar of honey unattended with some curious little boys was maybe not a good idea in the first place.

The Promise – The Crane Wife / The Fairy Crane

There are two similar versions of this tale that relate to Ken’s revised story. In The Crane Wife version, the bird is rescued by a hunter, then returns as a young woman that the hunter weds. The young couple struggle to make ends meet, so one day, the woman tells her husband that she’ll help by weaving cloth that they can sell – but the catch is that he must never peek into her room while she’s at her loom.

In Sakade and Kurosaki’s version of The Crane Wife story, it’s called The Fairy Crane. In this telling of the story, an elderly man rescues a crane that got trapped in a snare. The crane flies away to freedom and the man thinks that’s just his good deed for the day. But a short time later, a young woman comes to the elderly man’s home, where he lives with his wife and asks to spend the night. The couple never had children, so when the young woman reveals that she’s an orphan, the couple agrees to let her stay as long as she needs to.

Similar to The Crane Wife story, the young woman tells the couple that she will weave cloth that they can sell – but she makes them promise to never look inside the room while she’s at her loom.

In both The Crane Wife and The Fairy Crane versions of the story, the husband and the elderly couple’s curiosity get the better of them, and they discover that the young woman that they married / have adopted as their daughter is really a crane that is using its feathers to weave cloth. And in both stories, once the secret has been revealed, the crane tells her husband/her adoptive parents that she must leave.

Again, as a child reading these stories, I thought the endings were kind of sad, but well, what happened was punishment for not heeding the warning, you know? These crane stories are like the Greek/Roman myth about Pandora’s Box (where a woman opens a box that she’s warned to leave closed and unwittingly unleashes awful demons into the world), in that both are parables about the dangers of breaking a promise, or as that old saying goes, “curiosity killed the cat.”

Now, as a grown-up, I re-read those stories and thought, “Hey, was it really THAT bad for them to see the crane weaving? They did a good deed and just one moment of basically innocent curiosity meant that they had to lose forever someone they had grown to love? And what about the crane’s/woman’s feelings about all this? Was she sad to leave them or did she feel betrayed by their lack of trust? Who made the rules for this anyway?”

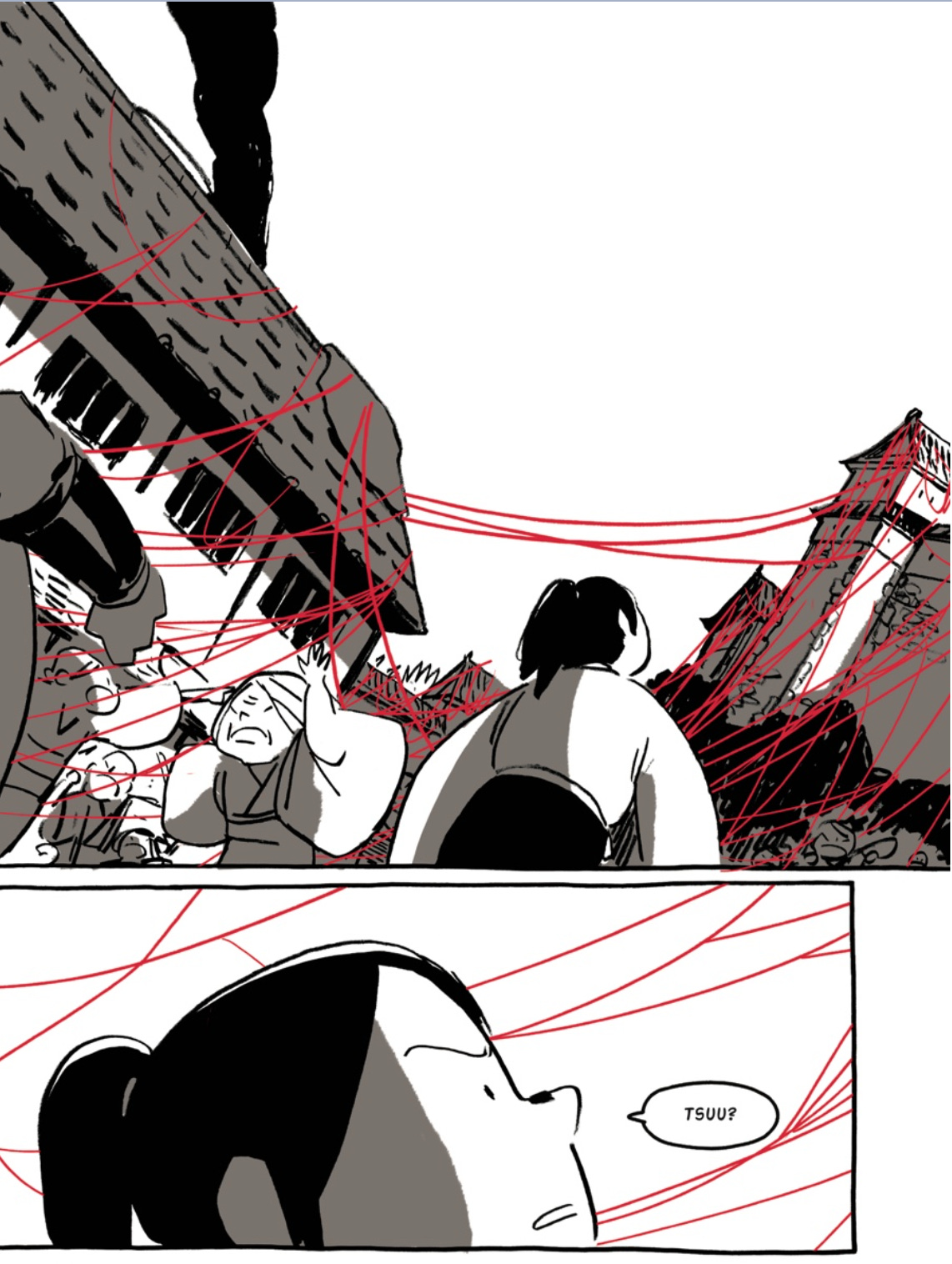

In The Promise, Ken provides a little more character development about Yohio, the poor but determined firewood seller who rescues a wounded crane, and Tsuu, the mysterious young woman who shows up at his doorstep on a snowy winter night. Ken adds just enough detail to make their love story a little more poignant.

But that’s not all that’s different – Ken introduces a villainous merchant who tries to exploit Tsuu’s talent for weaving cloth, and various other characters who are suddenly confronted with a kaiju-level threat that just might flatten their town and turn them into collateral damage in this fairy tale gone haywire.

I don’t want to completely spoil things if you haven’t read it yet, but it’s in this story that Ken uses the color red in a striking and dramatic way in this otherwise monochrome set of stories. Trust me – this is NOT how traditional Japanese folk stories usually end, but maybe they should?

Anyway, I hope I’ve tempted you to check out Never Open It: The Taboo Trilogy, and left a few surprises in store for you to enjoy when you do.

If you have read Never Open It, what did you think of how Ken tweaked, expanded the characters and maybe modernized the original stories? Are there other stories that would benefit from this kind of approach, or do you have other favorite fairy tales that have gotten a similar thought-provoking makeover? Add your thoughts and recommendations below – I’d love to hear about it!

-Deb Aoki

Definitely picking this up. Love that art and color scheme...and I've always been annoyed by those "gotcha" endings that punish people for being human.

Just placed my order with my local comic shop. Sad that i cant keep on reading this post. Thank you for all the great ideas you give me