The Origins of Unico, Tezuka's Lonely Unicorn

A look at the origins of this little blue unicorn and its many incarnations in manga and anime

by Deb Aoki

Once upon a time, a little blue unicorn named Unico entered our imaginations, thanks to the boundless creativity of Osamu Tezuka. Called “The God of Manga,” Tezuka was famous for creating many memorable characters and stories for kids, adults and almost everyone in between.

The story of Unico is centered around a little unicorn who has the power “to bring happiness to the pure and true.” However, this sweet and seemingly harmless ability catches the eye of Venus, the goddess of love. In a fit of jealousy, she commands Zephyrus, the West Wind to take Unico from his friends and family and doom him to a life of solitary exile. The West Wind takes pity on Unico and opts to instead to wipe his memories, then deposit the little creature in various places, across space and time. Each time, Unico makes friends, runs up against some fearsome villains and sometimes helps others find love along the way.

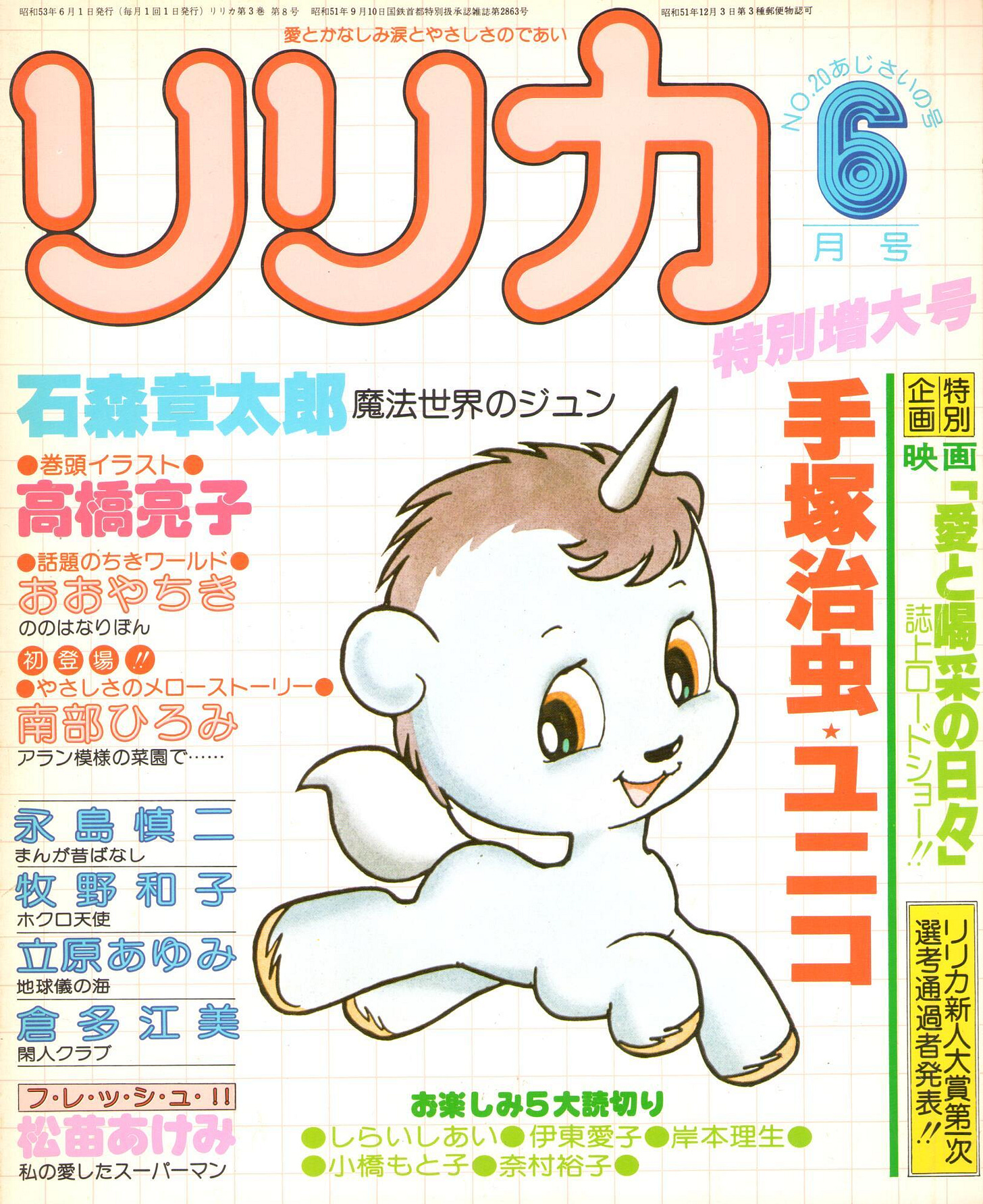

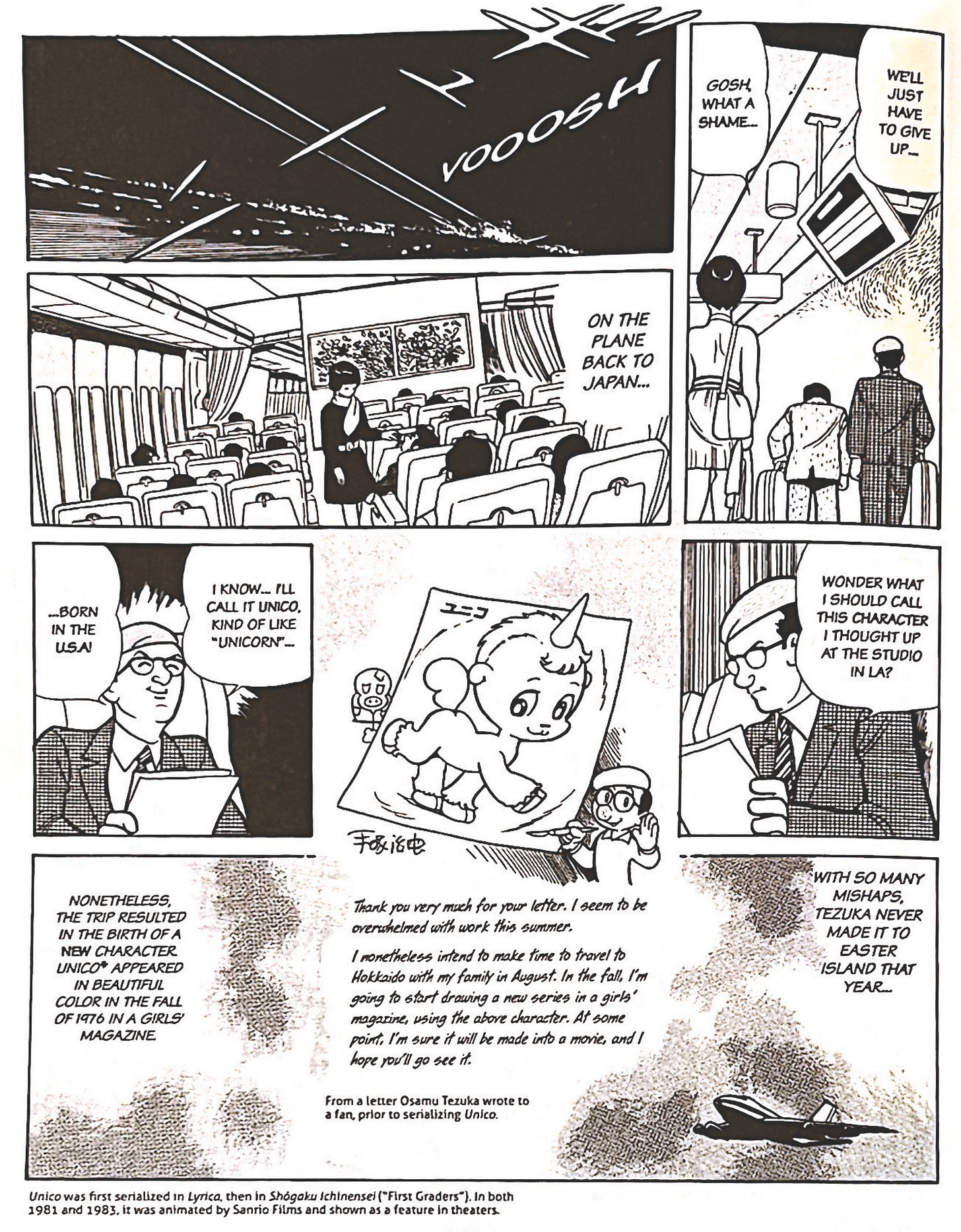

Unico was originally featured as full-color comic series in the pages of Lilica (Lyrica), a shojo manga magazine that was published by Sanrio, the gift and stationery company that created Hello Kitty. The first chapter of the manga debuted in November 1976 and the series continued until March 1979.

Besides a serialized manga series, Unico’s adventures were also adapted into animated feature films, The Fantastic Adventures of Unico (1981) and Unico in the Island of Magic (1983), as well as a 25-minute pilot episode for a proposed animated TV series.

Today, we’re interested in Unico again, thanks to the Unico: Awakening graphic novel that Samuel Sattin and Gurihiru are working on – but what’s the story behind the story of Tezuka’s little unicorn? The origins of this character, believe it or not, didn’t begin on a drawing table in Japan, but came about thanks to his visit to Los Angeles in June, 1976.

THE AMERICAN ORIGINS OF UNICO

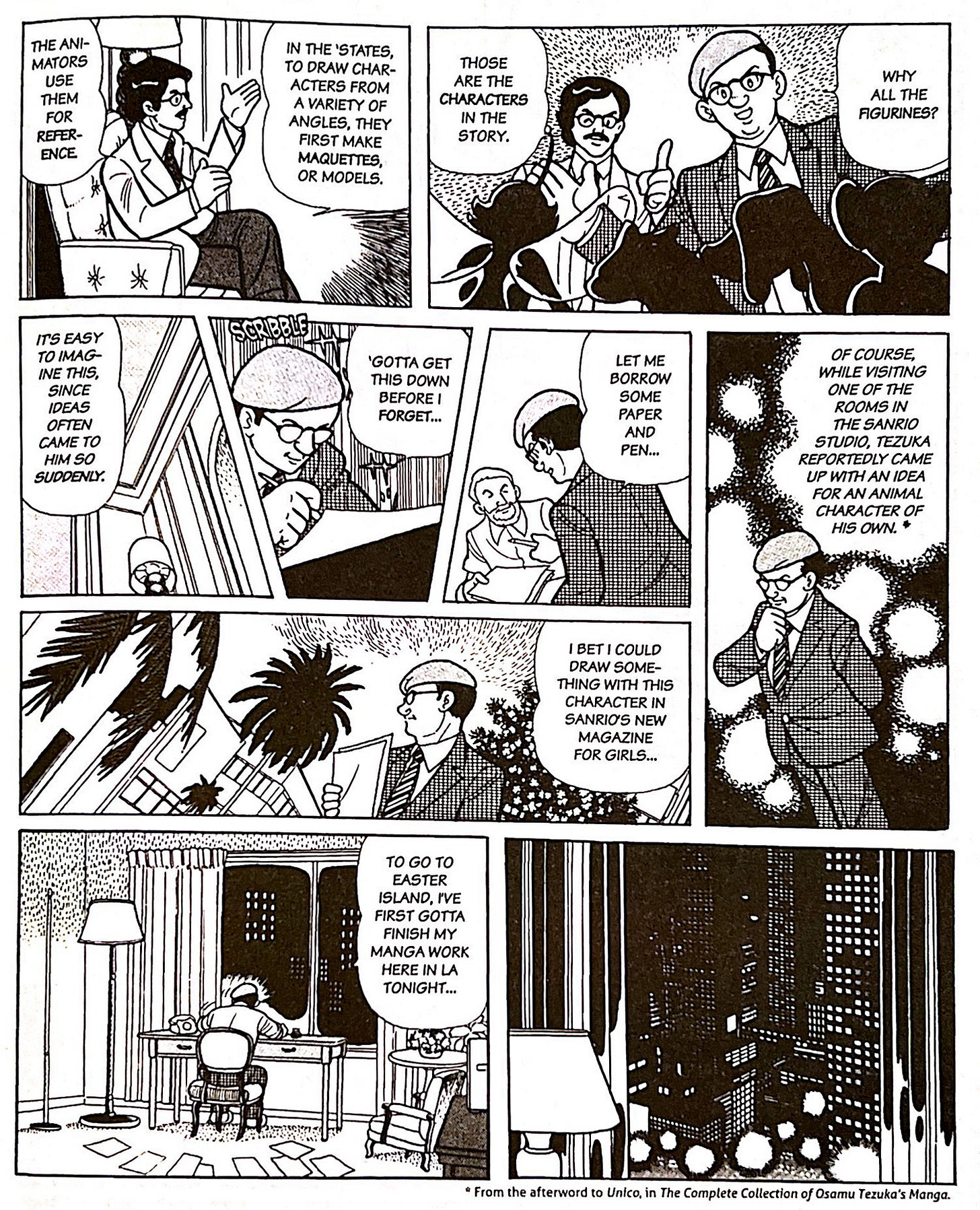

To understand how and where Unico was first conceived, let’s look at how Tezuka himself recalled the events that inspired the creation of this character:

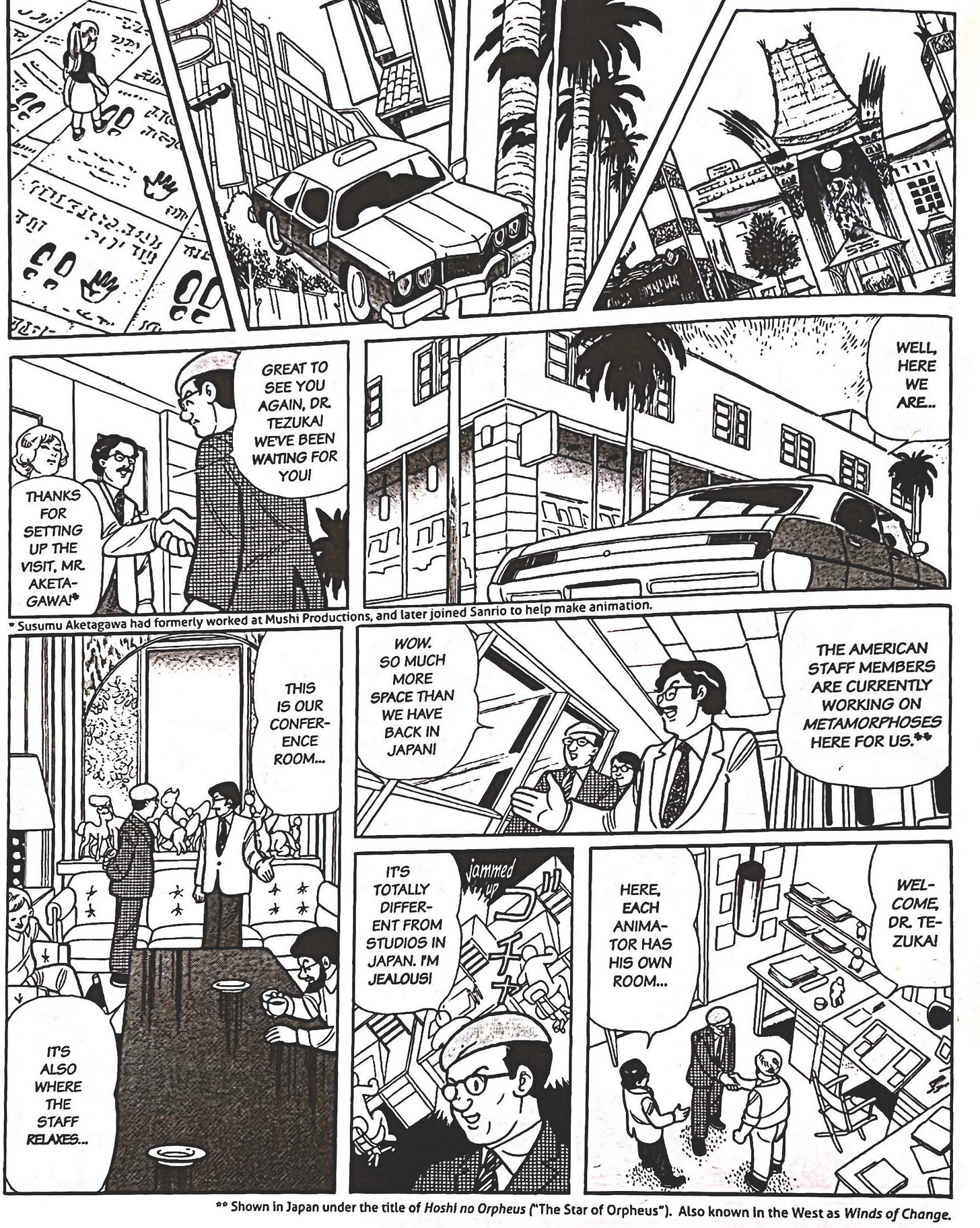

The character Unico was born in America. But it was not made by an American. A company that makes cute merchandise, Sanrio, started a studio in Los Angeles to make a (animated) movie Metamorphoses (later changed the title to Orpheus of the Stars/Winds of Change in English), with both Japanese and American staff.

When I visited that studio, a unicorn popped up in my head in one of the studio rooms. I asked for a paper and sketched while I had that image in my mind. That was Unico. There was a plan to publish a monthly shojo manga magazine Lilica and I was asked to do a series. But I have not worked on a shojo manga for a long time and I was thinking of doing a unique animal take, and then it suddenly popped up in my head in Los Angeles. During my flight back to Japan, I came up with the name “Unico” coming from unicorn, and had confidence, and I thought this will work.

-Osamu Tezuka, from Osamu Tezuka Manga collection, published in 1983, afterword from Unico

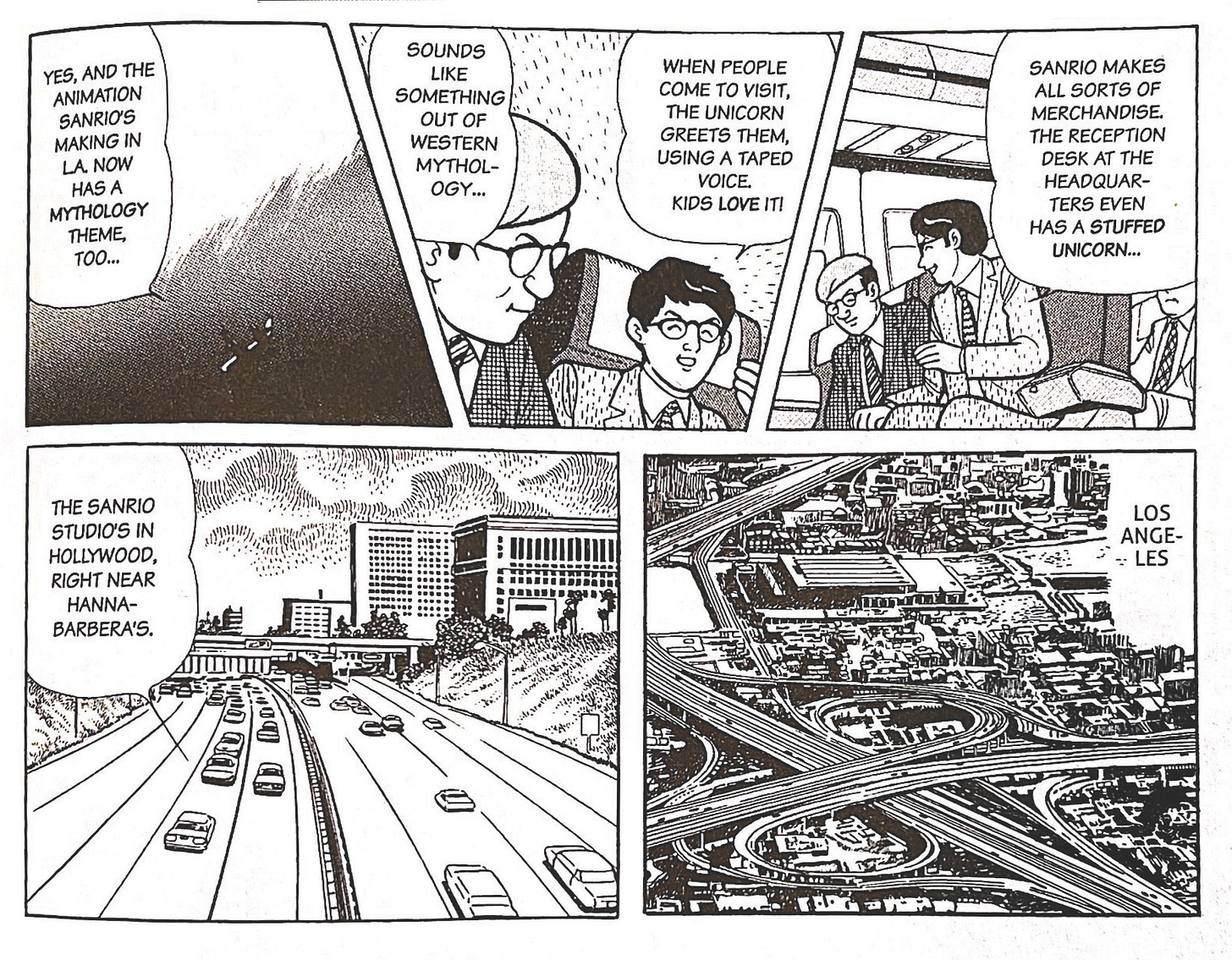

These events were captured in The Osamu Tezuka Story by Toshio Ban and Tezuka Productions (published in English by Stonebridge Press, these excerpts from pages 684-689)

In these scenes, Tezuka visits Susumu Aketagawa, a former employee at Tezuka’s Mushi Productions animation studio who had moved to Los Angeles to work with Sanrio and their animation production division. Impressed by what he saw on the studio tour, Tezuka was immediately inspired to create a new animal character that would become Unico.

SANRIO AND LILICA / LYRICA MAGAZINE

Founded in 1961, originally as the Yamanashi Silk Company, Sanrio today generates over $41B in annual revenue based on sales of stationery, toys and gift items, along with licensing of popular characters such as Hello Kitty, Little Twin Stars and Gudetama.

Magazine publishing is also part of the Sanrio empire. If you’re an old school Sanrio fan, you might remember the Sanrio magazines that used to be sold at their gift and stationery stores, like Hello Kitty Gazette or Strawberry magazine.

Another Sanrio magazine was Lilica / Lyrica, a monthly shojo manga magazine where the Unico manga was originally published. Lilica / Lyrica was different than other shojo manga magazines in that it was an all-color magazine when most manga magazines were printed with primarily black and white line art. The other major difference is that they bound on the left side, and the stories panels were laid out in left-to-right/Western reading order.

According to a representative from Tezuka Productions:

I heard that (Sanrio) did want to publish this magazine in English outside of Japan when they started. That is why this magazine started as a left binding, all color magazine that was initially for the Japanese market. The top manga-ka in both popularity and ability of that age was offered to work on the magazine and one of the top features was Osamu Tezuka and having his involvement from the start of the magazine.

Besides Unico, Lilica also featured stories by some of the era’s leading manga creators, including Tetsuya Chiba (Ashita no Joe / Tomorrow’s Joe), Hideko Mizuno (Fire!), Keiko Takemiya (To Terra), Moto Hagio (The Poe Clan), and special chapters of Jun, an experimental manga series by Shotaro Ishinomori, the creator of Kamen Rider.

This all-star line-up of talent didn’t guarantee Lilica/Lyrica’s long-term success, and it ceased publication in 1979 with its 29th issue.

Tezuka Productions offered this insight into the demise of Lilica/Lyrica:

We can only guess the reason why this magazine stopped publishing in 1979, but maybe it was because it was not made in traditional style (meaning editing the book and working the manga pages was not in traditional style), or because the Japanese readers could not get used to reading from left to right. We have not found any evidence of this magazine being published outside of Japan.

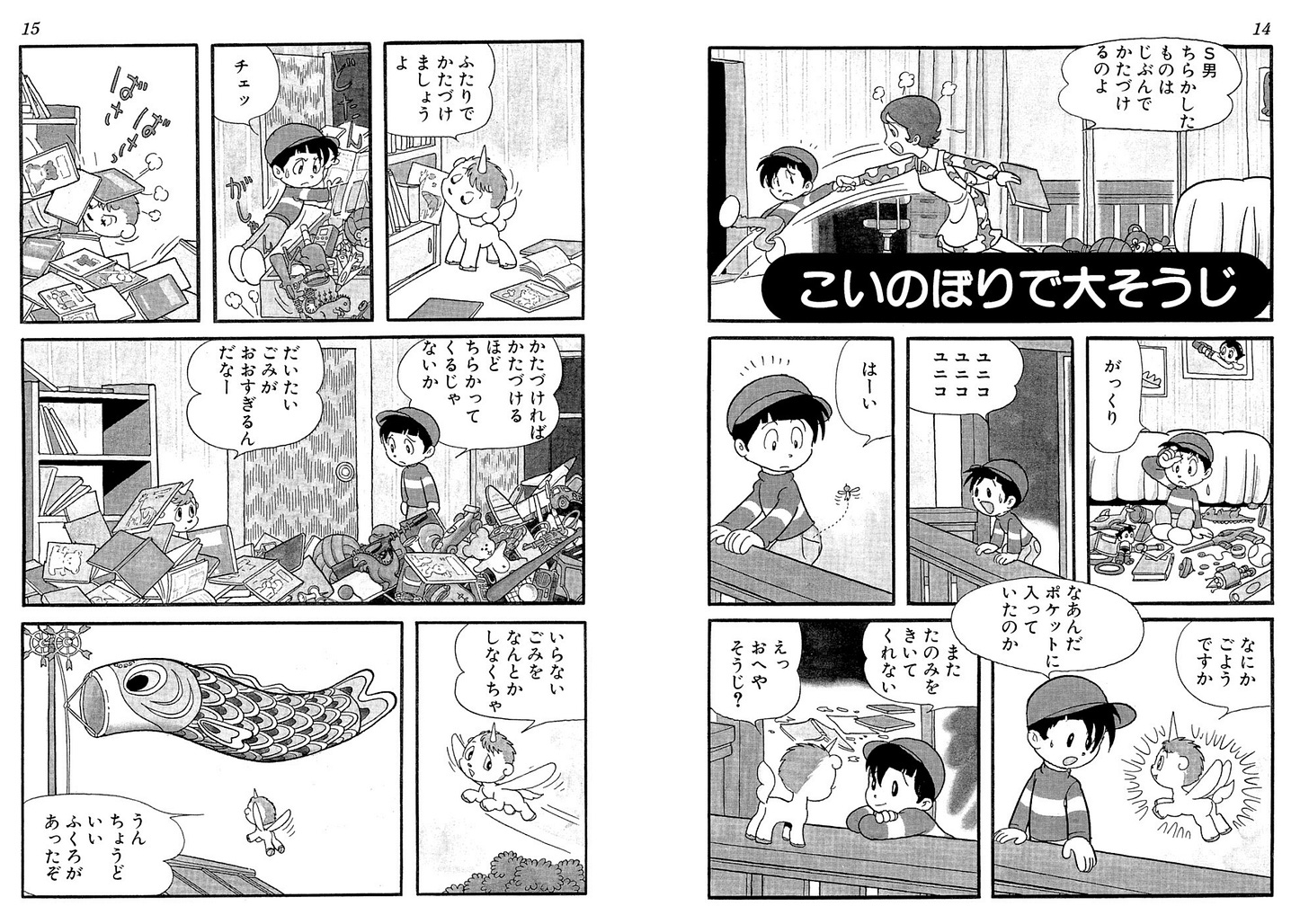

UNICO, THE SHOJO MANGA

When the first chapter of Unico appeared in Lilica (Lyrica) in 1976, Tezuka was also working on several other manga series, including Phoenix, the very dark, very adult drama MW, his manga biography of Buddha, his medical drama shonen manga series, Black Jack, fantasy adventure story The Three-Eyed One (as yet not available officially in English), as well as running his animation studio Tezuka Productions AND traveling overseas as an ambassador for Japanese manga and anime by visiting universities, movie studios, comics events, as well as pursuing various business ventures. Tezuka Productions has a fascinating timeline of his works here: https://tezukaosamu.net/en/manga/chronology.html. The Osamu Tezuka Story manga has more examples of how busy his schedule was at this time too.

Since Lilica/Lyrica was basically a shojo manga magazine aimed at young girls, there are definite shojo manga / romance themes in many of the Unico stories featured in this magazine. From the white settler girl Mary and Native American boy Tipi pairing in the first Unico story, Buffalo Hill, to the princess who falls in love with a prince from a rival kingdom in Rosaria the Beautiful, and the Cinderella x Crime and Punishment tryst between a thief and a police officer in 19th century Russia depicted in One-Night-Only Ball, love is the driving factor behind the drama in these stories, and Unico is there to help true love prevail… well, most of the time, at least.

Drawing romance or shojo manga stories wasn’t new for Tezuka – one of his most famous shojo manga creations, Ribon no Kishi or Princess Knight (available now in English from Kodansha) is a key example of his comics for young girls.

But Unico wasn’t just about this little unicorn acting as a mini cupid/matchmaker. Several of the stories in this original series featured mythical creatures and fantastical events from a broad array of eras. Having the West Wind deposit Unico into new places across space and time meant that at any given time, the little lost unicorn could find himself on the streets of a modern metropolis, pitted against a factory that is polluting its skies and waterways or in a magical fairyland, where Titania, the queen of the fairies turns him into a donkey, ala Shakespeare’s A Midsummer’s Night Dream, or even in a desert, answering riddles from a Sphinx.

But maybe to the surprise and disappointment of many readers, the final chapter of the Lilica Unico stories seems to leave the story unfinished. On its final page of Unico and Solitude, Zephyrus the West Wind appears, and whisks Unico away from his newfound friend, a little demon, without giving him a chance to say goodbye. Where the West Wind is taking him next, and whether Unico’s journeys will ever end is left up to the reader’s imagination.

If you’d like to read the Unico manga in English, Digital Manga Publishing offered a print edition via Kickstarter back in 2013 that might still be available here and there. Otherwise, their eManga digital manga storefront is offering a downloadable, full-color PDF of Unico too.

THE OTHER UNICO MANGA STORIES

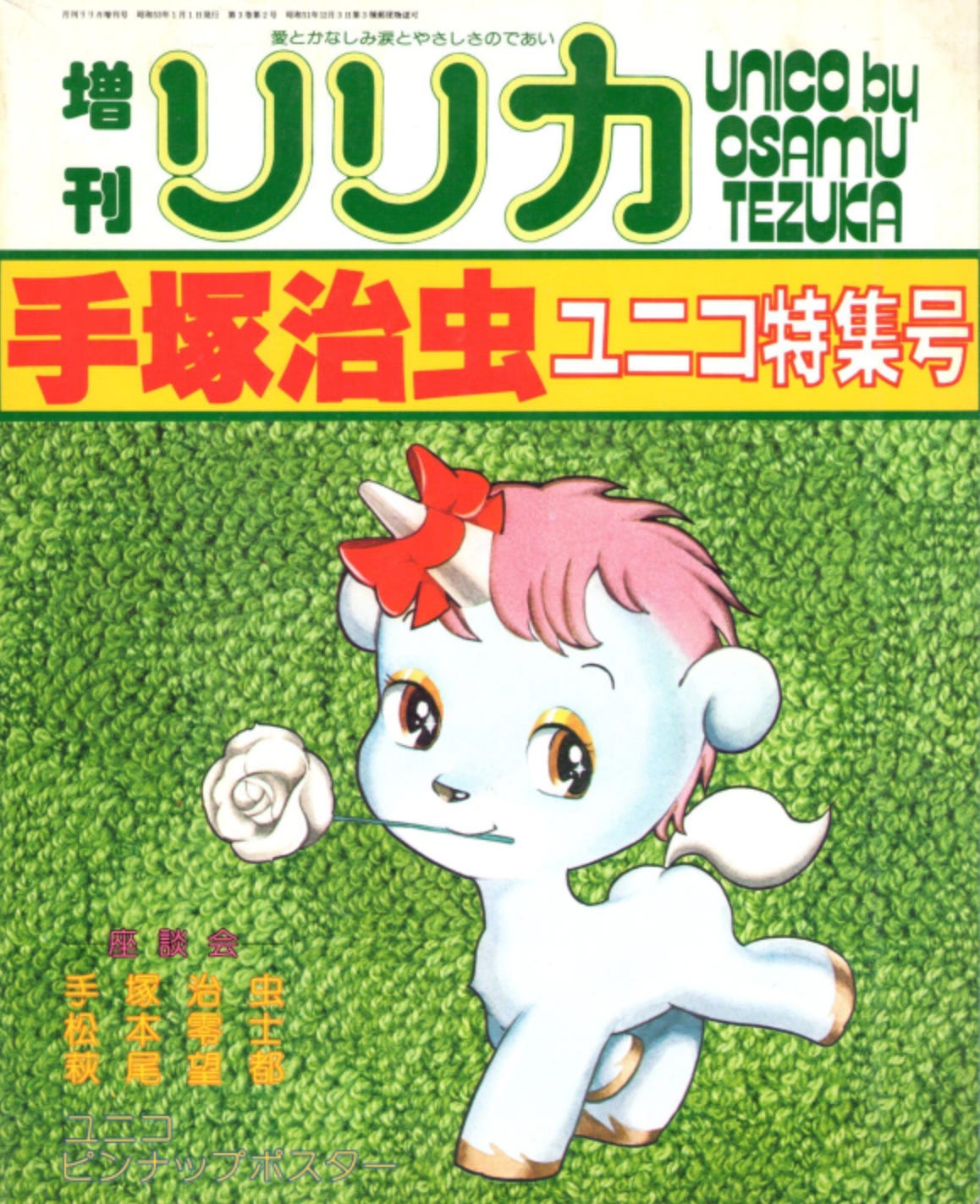

Unico was also later published in 1981 and 1982 in the pages of Shogaku Ichinensei, a manga magazine published by Shogakukan just for elementary school age readers, (specifically for first graders), presumably to coincide with the release of the Unico animated feature films.

These stories are different than the full-color Unico stories featured in Lilica/Lyrica, as they are formatted to read in Japanese right-to-left panel and pagination style, and are mostly in black and white (with some full-color pages). Since the stories were targeted for early readers, the stories are shorter, simpler, and maybe more humorous than melodramatic, content-wise.

In this series, Unico befriends a young boy named Esuo and Ragon, a baby dragon. Since Shogaku Ichinensei was a magazine for both boys and girls, there’s less of the shojo manga romance angle in these stories, and more about how Unico’s ability to grant Esuo’s wishes sometimes creates comical complications for humans and animals alike.

For example, in this story, Esuo is asked to clean his room by his mother, and Unico tries to help him by transforming a boys’ day carp banner into a fish that sucks up garbage.

But in the end, the fish does too good of a job, and ends up depositing a neighborhood block’s worth of debris right into Esuo’s yard. These adventures feel more like the comical misadventures of characters like Doraemon, Fujio Fujiko’s robot cat from the future than the time-traveling fantasy-romance escapades of the Lilica version of Unico.

The Shogaku Ichinensei version of Unico also features cameos by Chao/Chow/Katie the cat, from the Lilica Unico story, The Cat on the Broomstick, plus other Tezuka characters such as Astro Boy, Phoenix and even a cameo by Tezuka himself!

These stories aren’t currently available in English, but you can read a Japanese version of the stories in black and white from Bookwalker Japan. Tezuka in English has a little more info about these Unico stories and My Unico Fans had additional background info and some color screenshots too.

UNICO, THE ANIME

One key reason for the creation of Unico was for it to be a collaborative creation with Sanrio’s animation production division. From 1977-1985, Sanrio also created short films, straight-to-video anime, TV anime series and feature-length films, including two Unico feature films.

Metamorphoses / Orpheus of the Stars, which Tezuka mentions in his comments about Unico, had ambitions to be like Walt Disney’s Fantasia, with re-interpretations of famous Greek myths/fables such as Orpheus and Eurydice. It was produced in Hollywood and took three years and 170 animators to complete it for release. It unfortunately received dismal reviews and had a poor showing at theater box offices.

Here’s a trailer for Orpheus of the Stars, so you can kinda of see what I mean:

(I can’t believe this is a Sanrio production either!)

But looking at this very… well, sort of dark, not-exactly-kids-stuff-by-today’s-standards film, it does provide a little more insight into why when you scratch under Unico’s cute pastel color scheme and sweet expressions, there are much deeper, maybe a little-darker-than-you’d-expect emotional themes running through this series.

Tezuka Productions offered this insight into the anime connection to the creation of Unico:

According to the editor for Unico at Lilica, they wanted to make an animation with Unico from the get-go. In an interview held in 1983 when the second movie came out, that editor mentioned that and said that in the plan, Tezuka-sensei’s character elements were included.

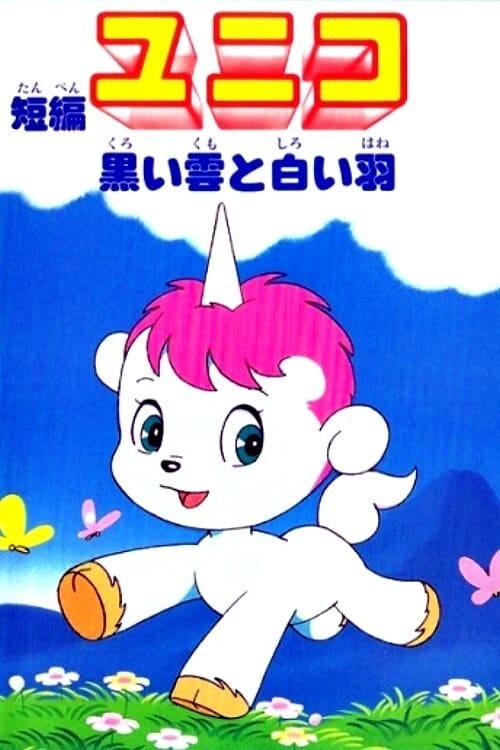

Back then, there were several plans such as feature length and TV series, but the first short film was made in 1979 based on the manga story, Black Cloud, White Feather.

Unico: Black Cloud and White Feather was directed by Toshio Hirata and was released in April 199 as a 25-minute pilot episode for a possible animated TV series.

In the English version of the Unico manga, the story is translated as Black Rain and White Feathers. Set in a modern-day city, this ecology-themed Unico adventure has our hero with hooves and a horn meeting a family of rats who have fallen on hard times, because the nearby river is polluted by a factory located upstream.

The rat family live in a house with Chico, a young girl who is sickly, along with her grandfather.

In a very Tezuka-esque sci-fi twist, the factory is run by an artificial intelligence that has fallen in love with Chico and tries to keep her prisoner. Unico comes to her rescue and whisks her off to a fairy land where she can dance among flowers and see the sun. Thanks to a magical feather that Chico receives from the fairies, Unico is able to help Chico and the rest of her town regain their health and happiness.

While a full TV series for Unico was never developed, two feature-length animated films were created, and released to theaters between 1981-1983.

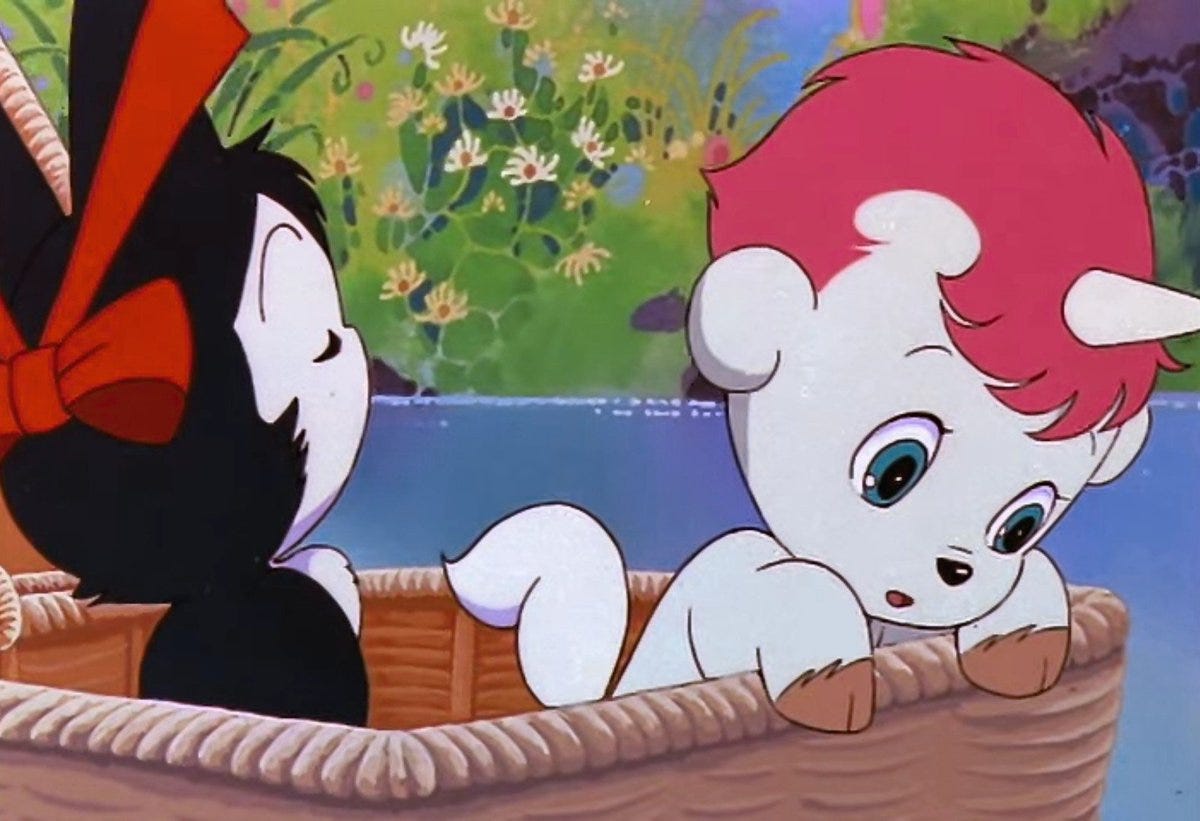

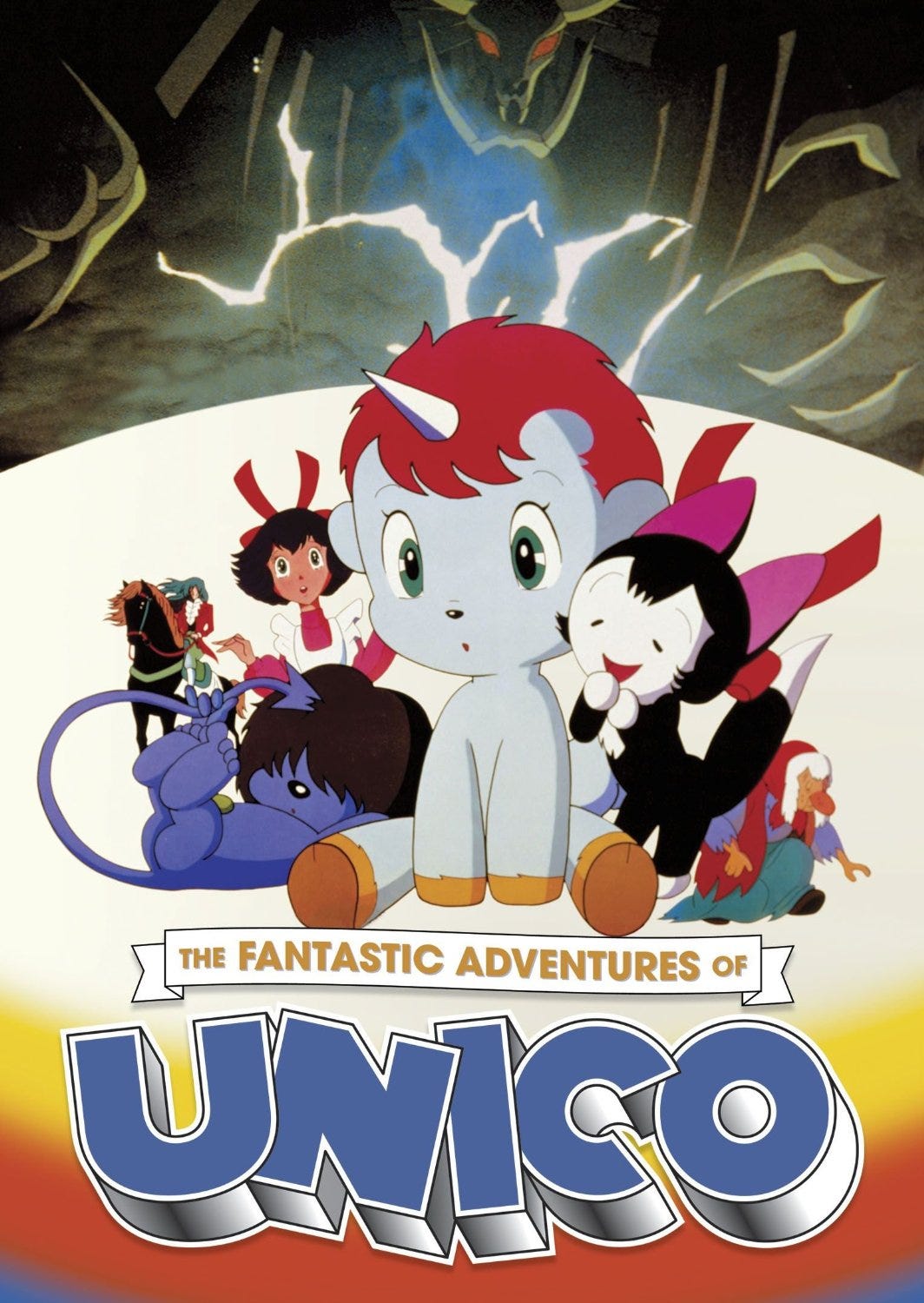

Unico, or as it was released in N. America, The Fantastic Adventures of Unico was released in Japan in 1981 as a 90-minute feature-length film. This film drew from two Unico stories, Cat on a Broomstick and Unico and Solitude, and introduced viewers to both Chao the cat and Beezle the little demon.

While The Fantastic Adventures of Unico was primarily aimed at younger audiences, it’s gained a kind of cult-status in N. America fandom thanks to multiple airings on The Disney Channel, and for the surprisingly sad fate that Unico is dealt at the end, where his memories are wiped clean and he’s sent to a new place to start anew. Erica Russell at Dazed makes a pretty convincing case for Unico as a “traumatising ‘80s cult anime about a lonely unicorn”

Bright, candy-coloured animation and simplistic storytelling aside, there’s a brutal bleakness to the world Unico inhabits and the fate he is subscribed to. While relatively “happy endings” are made available to the other characters the unicorn encounters, many of which are made possible by Unico’s magic, the lonely creature ultimately ends up being taken away from the friends and homes he has made, his memory wiped clean each time. It’s a sombre, jarring cycle, but not so different from the peaks and valleys of real life.

-Erica Russell, Dazed

In 1983, Tezuka wrote an original synopsis for another Unico feature-length animated film, Unico in the Island of Magic. The plot for this movie did not draw from the Lilica Unico stories, and instead depicts the Unico’s battle with Kuruku, a wizard who turns humans into dolls and makes castles using them as construction materials.

As Tezuka Productions describes this film:

One of the staff of the movie was Masao Maruyama, a legendary producer who was at Madhouse back then. (Maruyama started his career at Mushi Production and later established famous animation studios such as Madhouse and Mappa. He was also famous for sending out famous creators such as Satoshi Kon, Mamoru Hosoda, Sunao Katabuchi among many others.) When he worked on Unico in the Island of Magic, he wanted to make a classical animation style of Disney films with a mix of a feeling you get from (Steven) Spielberg and (George) Lucas movies, and he also said that he thinks he was able to accomplish that.

Meredith Woerner, writing for Gizmodo respectfully disagrees with this rosy assessment of Unico in the Island of Magic, going as far as to call it “the most horrifying children’s film ever made.”

You can decide for yourself! The Fantastic Adventures of Unico and Unico in the Island of Magic are available on DVD from Discotek Media as a “Unico Double Feature” DVD.

The Fantastic Adventures of Unico can also be streamed on Amazon Prime and on Tubi.

Unico in the Island of Magic is also available for streaming on Amazon Prime and Tubi too.

A more recent Unico animated feature, Unico: Saving Our Fragile Earth debuted in 2000, and is currently screened at Tezuka Osamu World in Kyoto Station.

Directed by Masayoshi Nishida, this original story has Unico meeting Tsubasa, a talking tree boy in a version of Earth where humans have drained it of all resources and destroyed the environment. Unico and Tsubasa go on a quest to make Earth habitable again, and along the way, they meet the Sphinx and a “time fairy” / a.k.a. Astro Boy who help them go back to the past to try to prevent this horrible fate. Learn more about this film from its page on TezukaOsamu.net.

UNICO TODAY

While Unico debuted over 45 years ago, it continues to enjoy popularity as one of Tezuka’s most adorable characters. To celebrate its 40th anniversary back in 2016, Tezuka Productions did several collaborative fashion, gift and accessory merchandising and promotional campaigns to offer a fresh look for the character for a new generation of fans.

Other contemporary manga artists have been inspired by Unico too!

Nagata Kabi, creator of My Lesbian Experience With Loneliness offered up her fanart of Unico:

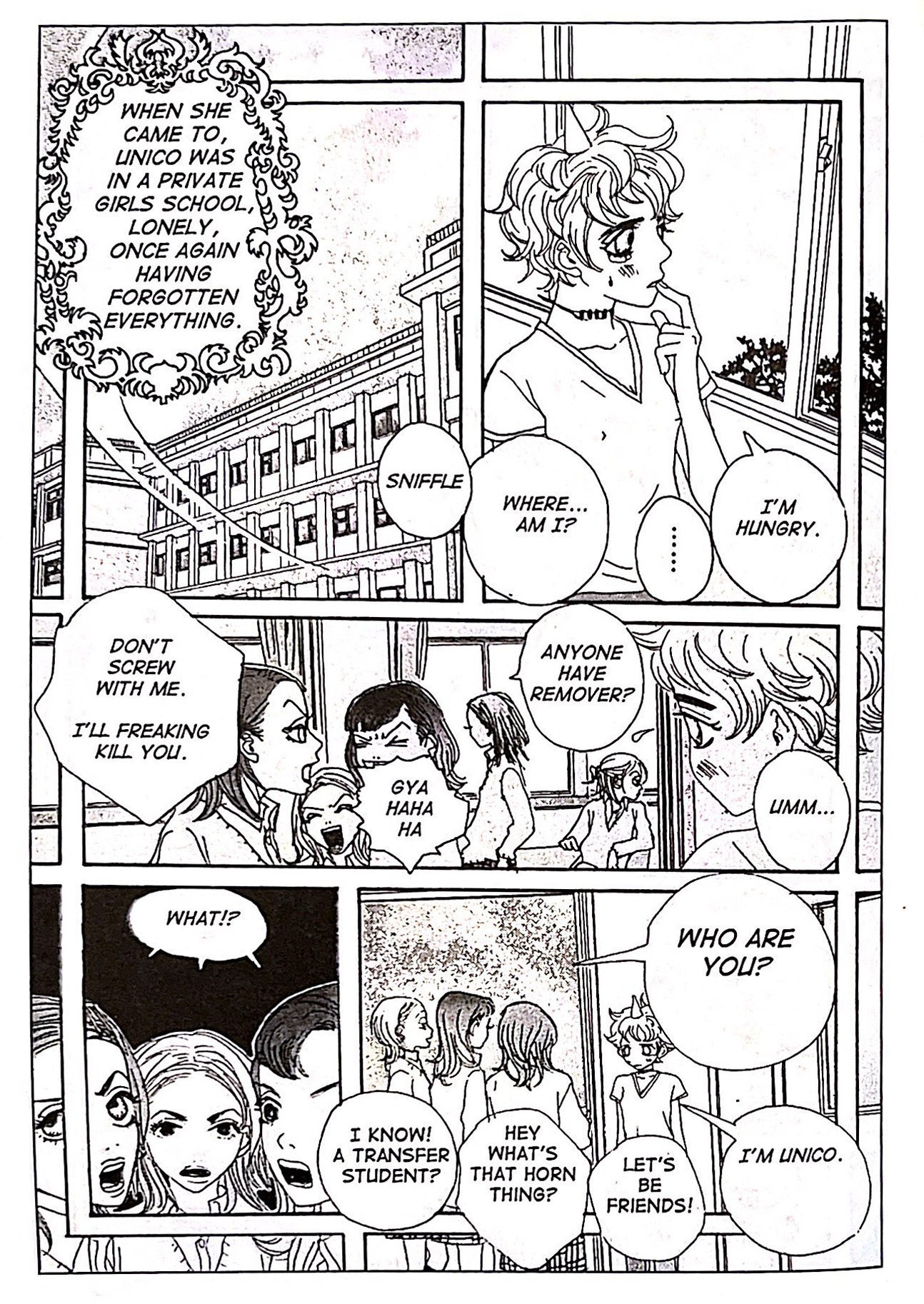

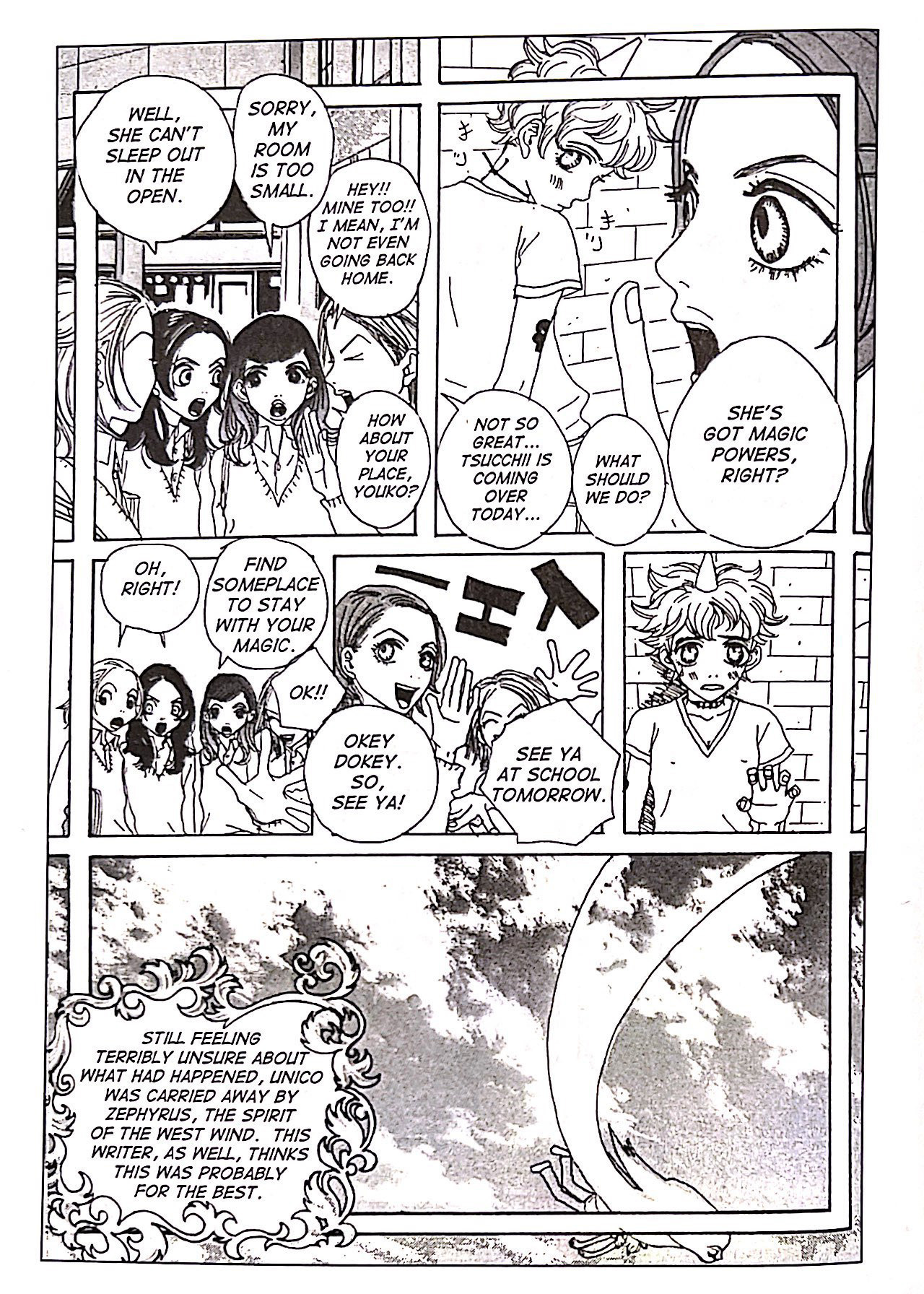

Moyoco Anno, creator of Sakuran and Happy Mania! also created this wickedly satirical take on Unico as a naïve girl in a Tokyo high school that was translated by Matthew Young, and published in Mechademia vol. 8:

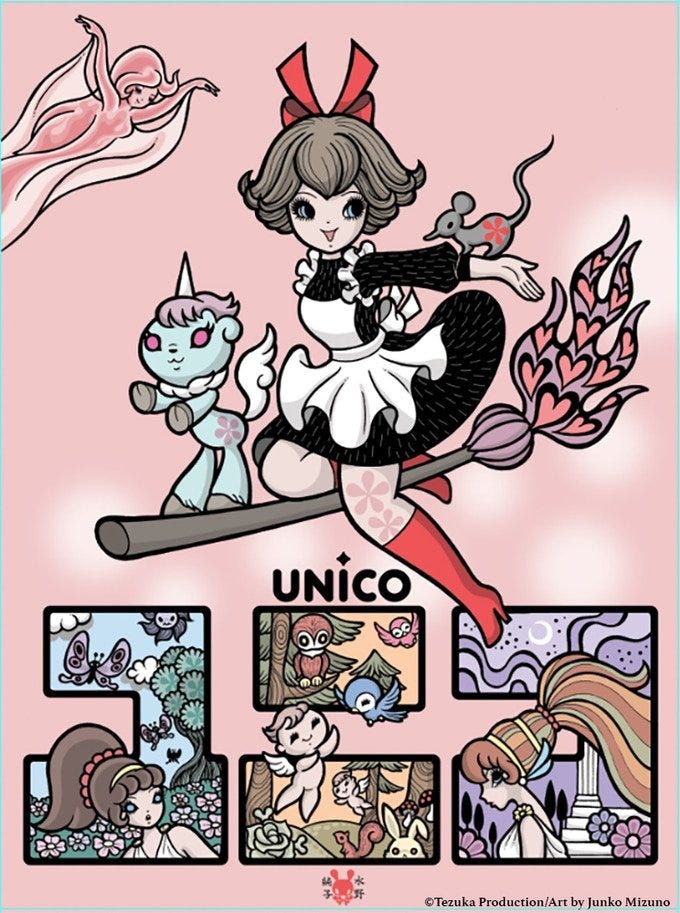

As part of the Unico: Awakening Kickstarter campaign, artists like Junko Mizuno (Ravenna the Witch), Peach Momoko (Demon Days), Akira Himekawa (Legend of Zelda) and Kamome Shirahama (Witch Hat Atelier) have contributed original illustrations paying tribute to Unico too.

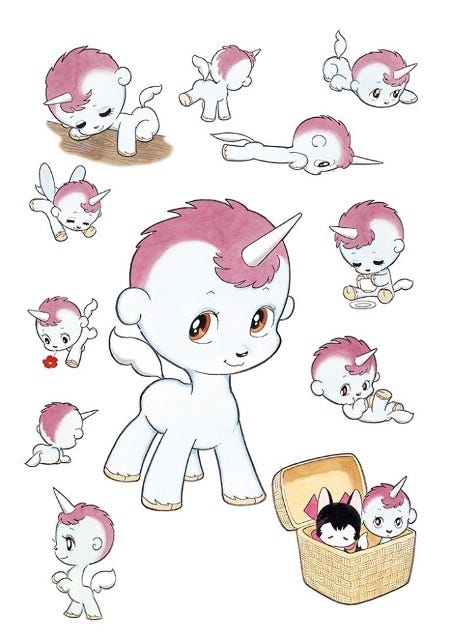

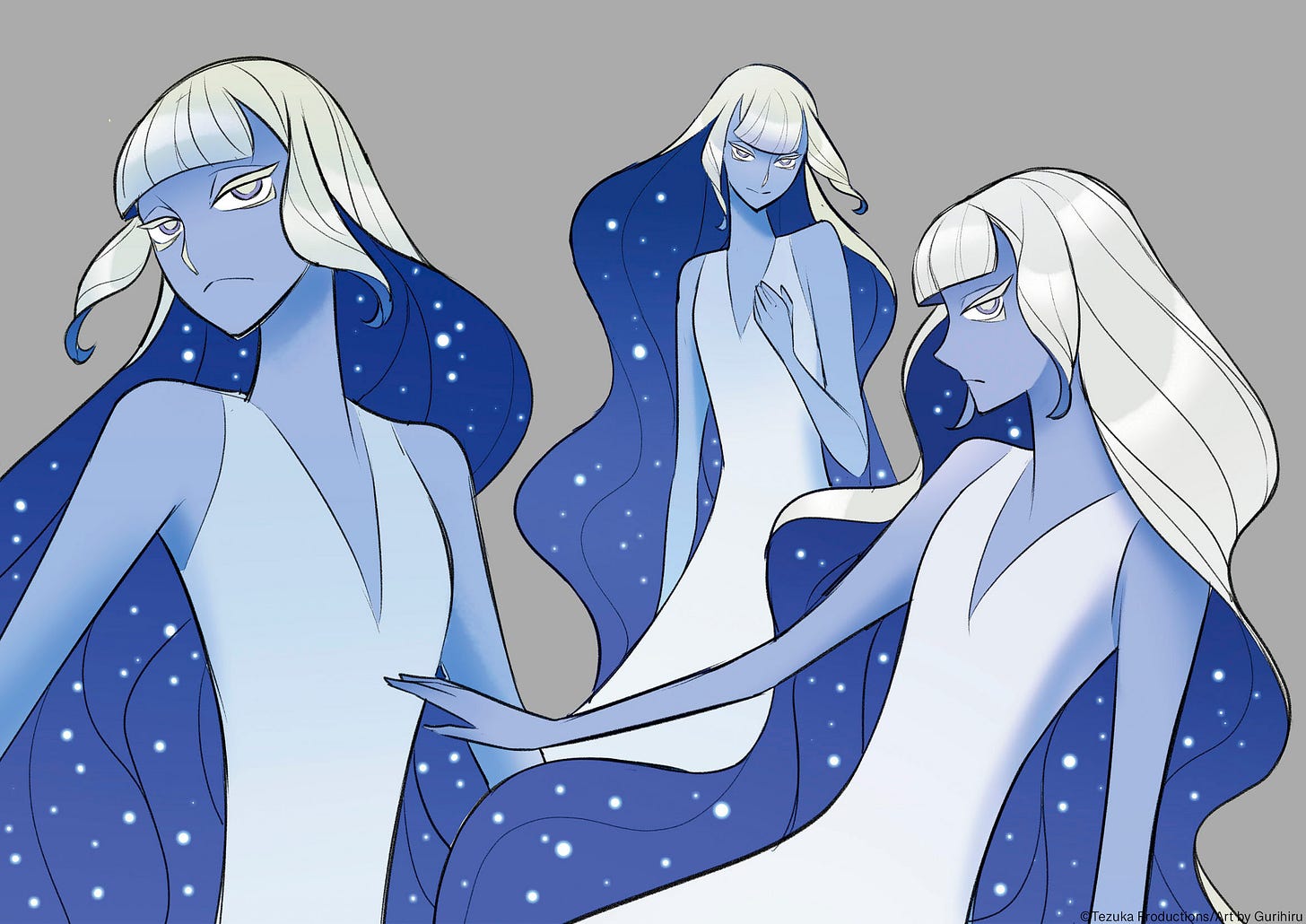

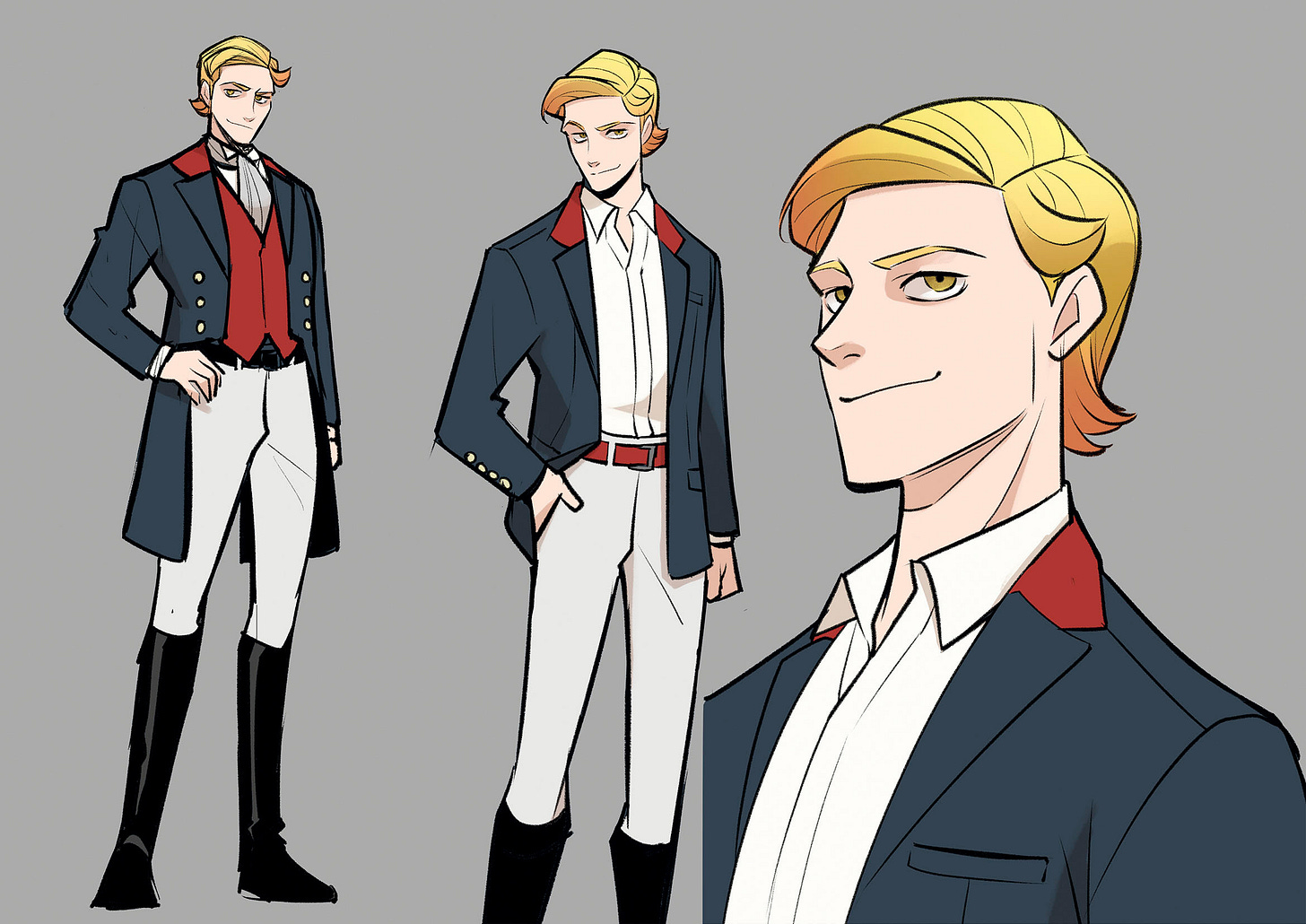

Also, to get a taste of how the character designs created by Gurihiru compare with the original versions drawn by Osamu Tezuka, here’s a side-by-side comparison of Unico, The West Wind, the Night Wind and Baron Ghost.

UNICO

CHLOE / KATIE / CHOW THE CAT

ZEPHYRUS - THE WEST WIND

THE NIGHT WIND

BARON GHOST / BYRON

So what makes Unico, a character created many decades ago relevant and ripe for reinvention? Tezuka Productions offered these thoughts:

While Unico is cute and innocent, it also has some loneliness, which is the true nature and essence of this character. It also adds darkness and deepness that will appeal to the modern readers. I felt that it has a great potential with its storytelling and characteristics. Gurihiru’s art has both nostalgia and freshness which gives us the newly reborn Unico that will be loved by readers instantly.

There’s still time to get in on the Unico: Awakening Kickstarter campaign to get your copy of the upcoming graphic novel, along with some of the exclusive goodies, t-shirts, prints and more.

ICYMI - here’s our interview with Sam Sattin, co-creator of Unico: Awakening, as a special Mangasplaining: Listen to Me segment from episode 62: My Love Mix-Up!.

If you’re already a paid subscriber to Mangasplaining Extra, thank you! If you’re a free subscriber, consider upgrading and becoming a paid subscriber. We’re working hard behind the scenes to bring you even more great, new exclusive manga and articles, so stick around, there’s lots more to come!

I hope this is the first of more "global manga reboots." I'd love to see artists swoop in and finish some of Tezuka's unfinished works, too.

Great write-up! I had no idea the Unico manga was still available in English (digitally, anyway).

BTW, both Unico films are free to stream on Retrocrush: https://www.retrocrush.tv/search?s=Unico

Just the dubs, though.